This week, or last week I should say, I spent considerable time researching for my upcoming paper, “Know-How and the Incessant Energy Diet”, to be featured at AESP’s National Conference in San Diego – get your tickets and reserve your seat today. In doing so, I read a few evaluation reports for retrocommissioning (RCx) – the program of choice for the paper.

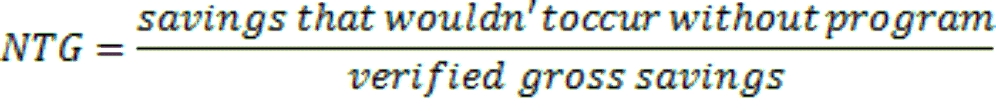

When I arrived at the attribution section, as in, what are the savings attributable to the program, I scoffed at the findings. For a refresher on terminology, refer to recent post Energy Program Evaluation Asylum. I didn’t scoff at the findings of the evaluator, I scoffed at the weaselness of stakeholders interviewed to arrive at the net-to-gross ratio, or NTG. To clarify NTG, see the equation below.

At some point, I’ll do an entire post on the bogusness of net to gross and free ridership. One reason for the bogusness is: people lie. That is correct. I don’t apologize for offending you because it is simply true.

Take for example a recent article I read in The Wall Street Journal entitled, Why Men Lie About Their Height. The crux of the article is many (millions) men lie about their height and report that they are exactly six feet tall – apparently, because it’s like the millionaires club, but also, thugs and bullies don’t pick on guys who are six feet tall – the John Wayne and Clint Eastwood types.

In another article, The Case for Lying to Yourself (that’s right, people do it all the time), research showed 25% of college bound students rated themselves in the top 1% in their ability to get along with others. When people are asked to choose the picture that best represents their appearance – you guessed it, they pick one that is most attractive. Guys don’t need a personal trainer because they are “in control” and can slim down whenever they want, except suddenly, they find themselves looking at their pudgy gut at age 50. Uh-oh.

In another study, students are given matrices of numbers with two decimal places to the right of the decimal point. They are asked to find combinations of numbers that add to 10.00. One group takes the test and reports their answers on the sheet of paper, and they average four combos of numbers that equal 10.00. Another group is instructed to count their own findings and then shred the paper. Miraculously, the latter group averages six instances of 10.00. Uh-huh.

In energy program evaluation, both process evaluators and impact evaluators must interview multiple stakeholders – customer, contractor, consultant, account manager, program manager, and even different people among these groups (say decision maker versus wrench turner) and triangulate to the best guess. One thing is for sure – there is a tremendous gravitational pull of bias in favor of oneself.

Enter RCx attribution reported by the evaluation. The NTG survey results can be summed up as follows:

- Participants (customers / end users) would have implemented the measures anyway

- Service providers (RCx agents) are growing their RCx business but the program has little impact on that

It reminds me of this quick clip from Top Gun and roosters taking credit for the sun each morning.

I’ve spent 17.4 out of 17.8 years of my career trying to figure out how people make decisions about energy efficiency, and I think I have 6.2% of it figured out. About five percentage points of that is why customers do RCx projects. The answer: save energy – reduce operating cost. Period. The measures would not happen, or would not happen as soon, in absence of the program.

Retrocommissioning is all about fixing stuff, improving comfort when there are problems, and saving money. It does not include purchases of shiny objects that people vaguely understand – like boilers, chillers, windows, and light bulbs.

Secondly, if participants would have done a measure anyway, what was stopping them? These are low-cost, no-cost measures. Maybe this should be a follow up question for the interviewer: “Why didn’t you implement the measure, Obi-Wan?” The answer: they didn’t know it existed at the time of the investigation. This is due to lack of time to investigate their own facility, or lack of expertise to realize a system is wasting energy and how it can be made to operate with much less energy consumption. Either way, the program moved the measure much closer in the future, time-wise, or the diamond in the rough would never be found.

The contractor or customer may very well have bought the 92% efficient condensing boiler or LED light fixture in absence of the program. The very existence of RCx measures that are identified and implemented as a result of an RCx program indicates there was a barrier to getting the job done, and the program mowed down that barrier.

About the knowledge barrier – I tend to agree, and am reminded of Christopher Columbus, whom I thought about exactly once per year for five minutes while enjoying the day off of from school: ‘“Anyone could have done it”, critics argued upon the return of the explorer Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) from having discovered ‘The New World’. In response, Columbus challenged them to stand an egg upright on the small end, and when they failed he carefully cracked the shell and stood the egg up. “But that’s easy!” they exclaimed. “Yes”, replied Columbus, “once you know how.”’

There are some great questions and hard challenges in this rant. One of the first thoughts that sprung to mind is to keep error bars in mind; they are large. In impact evaluation engineer world, we might use 15 calibrated loggers to determine the verified savings on a building with 100 new lighting fixtures. At the end of an evaluation, we may have looked at 10s or 100s of individual projects and deployed 1,000s of data loggers. In the end, we may or may not hit 80/20 or 90/10 results, depending on the variability of the verified v. claimed savings. This is without accounting for the fact that there may be as much as +/- 2 percent errors on calibrated power meters, unreported production variance at the facilities under examination, and limited modeling precision that drive down the certainty of each individual project we look at.

These problems are far worse for NTG studies. I have yet to figure out how to put a lighting logger on an accountant and record their free-ridership rate (I am still working on this though). I am going to go out on a limb and suggest that there is more than 2% error in the individual NTG survey. It is hard to quantify NTG, but people generally do the best they can with the data they have. NTG is important; giving away money for nothing, and collecting admin fees to do it, is bad policy. NTG is the best we have to do this, you have to interpret it with tons of salt.